Ankeny Schools is a thriving community residing within the beautiful sprawling suburbs of Ankeny, Iowa. The district houses over 12,750 students, 78.8 percent of which are white. Though Ankeny has found an increasing amount of diversity over the past five years, it can be reportedly difficult for Black, Indigenous, or other People of Color (BIPOC) to find a community.

Student Experiences

Ale Cabello, a senior and Japanese-Latina student at Ankeny High School (AHS), grew up speaking two languages.

“The only thing I don’t like about being here is I can’t really relate to people because you don’t see a whole lot of people of my ethnicity or people who live in Mexican households,” Cabello said. “I feel like it’s more difficult for me to communicate.”

Senior Richzzi Danielle Monteverde felt the same way when she first moved to Ankeny from Davao City, Philippines.

“The language difference was definitely something I had to overcome. In elementary, there were a lot of times where my dialect wasn’t exactly perfect compared to the kids, and I would get made fun of because of that,” Monteverde said.

She believes others may act this way because of a lack of exposure.

“I have a mindset that’s more accepting because I personally feel like I’ve experienced more compared to people that have lived here their whole lives,” Monteverde said. “Sometimes you encounter people that are a little bit more close-minded because they haven’t experienced different cultures.”

“The way the community is set up [feels] like a bubble. It’s a little bit isolating because sometimes I realize when I look around there’s not a lot of diversity or welcoming communities or different types of cultures. So at times I feel like I stick out,” Monteverde said.

Even between the different suburb cities, the cultural shift is noticeable.

“I used to go to school in Des Moines. At the school I went to, it was really enforced to be respectful to everybody you know. Bullying was not tolerated whatsoever,” African American AHS sophomore, Gabriel Brannon, said. “But in Ankeny, any kid will say anything and they’re not going to get in trouble. Nobody cares. Because it’s just the culture here.”

Cabello lived in Des Moines for a period of time noticing less diversity after moving to Ankeny. And with an increase in diversity comes an increase in exposure. In a community that lacks that kind of diversity, BIPOC have to seemingly struggle with more ignorance around them.

“Every once in a while if I’m talking about something I enjoy eating, people will be like, ‘That sounds gross. That’s disgusting.’ It’s really humiliating because I feel like I can’t talk about these things without being judged,” Cabello said.

Insensitive jokes, comments, and microaggressions are reportedly common occurrences that BIPOC students face.

“This is a very privileged – and mostly white – community,” Brannon said. “Some people don’t know how privileged they are. People say the n-word all the time. It’s just something I hear now, I guess. And even if it’s not directed at me, just in general people will say it because they think they’re being funny, but it’s not.”

For students of color, they have to learn to deal with it, go along with the joke, or ignore it.

“I used to laugh sometimes about the jokes because I thought they were a little bit funny, but the more I think about it, the more I’m like, it’s not. It’s messed up that our culture has come to this point where people will say anything,” Brannon said.

Even with the exponential growth of the BIPOC population in Ankeny, racial discrimination is still prevalent. That’s why Ankeny Schools has been working to implement more Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) programs.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI)

in Ankeny Schools

Over the past five years, Ankeny Schools Superintendent Dr. Erick Pruitt and Chief Diversity Officer Ken Morris Jr. have worked together to create a DEI framework equipped with equity goals. These goals will help teachers be more strategic about the content that they teach.

“In my first year with Ankeny, our leadership team engaged the community in a process to create a new Strategic Plan, a Graduate Profile, and the DEI Framework. Our diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts are not separate from the rest of the district’s work but rather embedded into it,” Pruitt said.

That involves a system that focuses on identifying, responding to, and educating about bullying and discrimination.

Pruitt says that all of the district’s work is anchored in three principles:

Supporting student learning (Strategic Plan Pillar 1: Rigorous & Relevant Academics; DEI Framework Objective: Effective Instructional Practices & Procedures),

Supporting staff (Strategic Plan Pillar 2: Talented People; DEI Framework Objective: Effective Leadership), and

Supporting students and families (Strategic Plan Pillar 3: Supportive Environments; DEI Framework Objective: Effective Parent and Family Engagement).

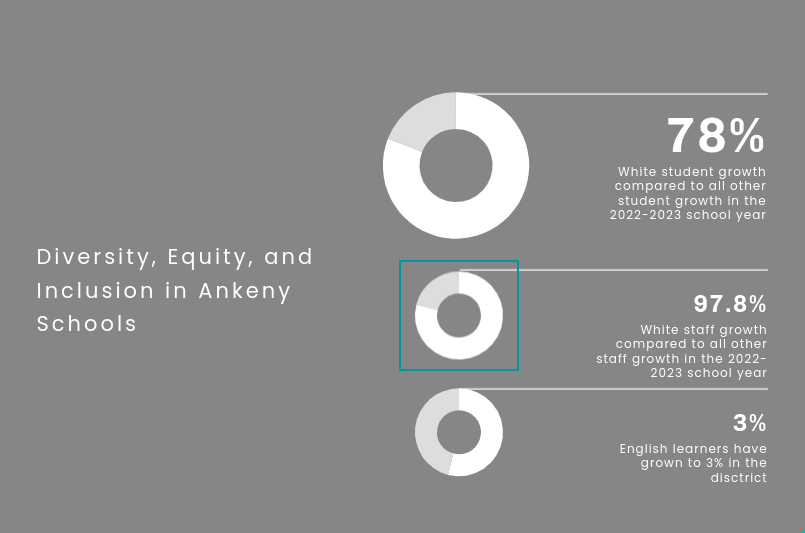

Since the year 2000, the percentage of non-white-identifying students rose from 3.5 percent to 21.2 percent in 2023, according to district data.

“Our school district has reflected the community and our community is becoming more and more diverse,” Morris Jr. said.

Accompanying that growth are noticeable changes in attitude among the student body.

“What’s been really interesting and exciting at the same time, is that in the five years that I’ve been in Ankeny, I’m starting to see students develop more agency in their experience and begin to ask more of the school district in terms of supporting that they need to improve their experience,” Morris Jr. said.

Morris’ title includes facilitating professional learning for administrators and staff in the Ankeny Community School District. Using data, he looks for gaps in policy to improve upon in compliance with state and federal laws.

“I think that for a long time, adults would develop what they believed was the best environment for students to grow and to learn. And what I’m finding here in Ankeny and other places is that students want to be a part of those conversations, they want to have an active role and co-create the type of culture they want,” Morris Jr. said.

Staff demographics is another area for growth, he says.

“I think there’s an opportunity for us to identify competencies in our hiring that would reflect the demographics of our student body. [We can] create processes that remove bias so we can identify talented people that are reflective of all the dimensions of our students identities,” Morris said.

From 2000 to 2023, the growth of non-white staff members has grown from .9 percent to 2.2 percent. Compared to the student growth demographics, it is seemingly lacking.

Impact of Discrimination

The first instance of racial profiling that Morris Jr. can remember happened when he was 16. Morris Jr. grew up in Peoria, Illinois, where he was known as a good student, football player, and church kid. He had never known trouble.

“At a young age my dad always taught me about what to do when you’re stopped by the police. I was very young, and I didn’t understand why we was having this conversation. At 16 is when it finally happened, everything that he taught me kicked in, and I was scared. I was pulled over by the police. [The police said that] my car was similar to a known drug dealer in town. They said they pulled me over because they thought I was him,” Morris Jr. said. “I just thought that was so funny because my car was so raggedy. They asked me if they could search my vehicle, they didn’t have the right to, but I was scared to tell them no. They handcuffed me and made me sit on the curb as they began the search, to which they didn’t find anything.”

Morris Jr. has always been interested in diversity work. In college, he was involved in various diversity groups. He graduated from Monmouth College with a Bachelor’s in Student Services with a focus on multicultural affairs. Following that, he received his Master’s in Educational Leadership from Western Illinois University.

Before coming to Ankeny, Morris Jr. held multiple DEI-centered positions at Cornell College, the University of Iowa, and the Cedar Rapids Community School District.

“[There are] very little to no resources for the work,” Morris Jr. said. “When I was in higher education, the institution would have all these glowing statements about their commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion, but there were very little resources to match those statements. So it was incongruent.”

Bringing up these issues themselves was a challenge.

“It could be misconceived as you attacking a person or department and saying that they’re doing something wrong. And it’s quite the opposite. It’s just saying that we have our data informing us that we have groups of students that are not having the same level of success – or they may not have the same experience – as maybe the majority of our students,” Morris Jr. said.

He says that it can be especially difficult leading work as a person of color.

“And I think that that creates friction because you have staff, sometimes students, who have these really ugly experiences that they go through constantly or have experienced on more than one occasion. And you may have someone who hasn’t, and it may be easy for them to dismiss it because they haven’t experienced it, thereby making that group of people feel invisible,” Morris Jr. said.

Speaking for himself, Morris Jr. has had drastically different experiences from his peers.

“There’s adults that have never been stopped by the police at all. I have been stopped by the police more than I care to share because of my race,” Morris Jr. said.

Working as one of the only black staff members at AHS, math interventionist Davena Johnson has felt the same feeling of isolation in her community.

“[During COVID], I came in one day and somebody black had been murdered again by police. I don’t remember who it was, but I came in heavy. And most days, especially the first year, I felt like I had to check my blackness at the door, right? Like there isn’t anybody in this building that cares about another Black man being killed,” Johnson said.

Growing up in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Johnson was surrounded by a diverse community, but coming to Ankeny was jarring.

“It is very isolating to be a person of color in a very white space. At least at Cedar Rapids, I see Black people every day. Now as an adult, I’m usually the only Black teacher in the building,” Johnson said.

Johnson has made a constant effort to share diversity with students and teachers alike.

“I’ll take like a couple days a week to talk about whatever’s on [the news] that day. And we will have rich conversations about things,” Johnson said.

She teaches history that most classes would not teach as extensively, such as Claudette Colvin, a student part of the bus boycott movement who preceded Rosa Parks.

“So [I share] all of these things that people don’t normally know unless somebody teaches you, which is what schools should be doing, and then they go home and share that,” Johnson said.

When she first came to AHS, Johnson led a book discussion over the book, “Me and White Supremacy” by Layla F. Saad.

By the time she was done, her book discussion had blown up.

“I had about 60 educators, admin, principals who were buying it for anybody in their building,” Johnson said. “I put myself out there to try to educate and build allies. I need teachers that are aware and cognizant that excellence comes in all shades. Right? And if you’re a teacher that grew up in Ankeny and you’ve never experienced anybody that doesn’t look like you, that might be very hard for you to understand and acknowledge.”

Having worked previously at Southview, Johnson is now trying to bring her efforts to AHS.

“I mean I’ve only been here this school year and only half-days the first semester, [but there is] definitely more assimilation here,” Johnson said. “I feel like at Southview, Mr. Allen and I did a good job of giving students a space to be.”

At Northview, Renee Potts, an associate and retired teacher of 29 years, has been leading efforts for the Northview Student Union (NSU).

“My approach is to just wanting everyone to be able to come and be a part of and learn about culture. That’s the way I feel when I came here. It’s not an effort of us against them. It’s about being able to appreciate the various cultures within our community and being able to develop that understanding as well,” Potts said.

Her group organizes various events, such as guest panels, the World Culture Fair, and hangs up bulletin boards around school celebrating different cultures. The NSU now consists of around 20 members, but it was not always receiving that amount of engagement.

“Nobody would show up, and sometimes I got discouraged. I’m like, ‘Okay, I think I’m done after this year, because I’m not getting the response.’ But having that thought of, ‘What if I was not here, then who would it be?’ And it’s got to be us. It’s got to be me being able to step up and being that pioneer,” Potts said.

For Potts, any amount of engagement means growth.

“Even if I have one or two students who stop and read our bulletin boards and things like that, I feel I’ve accomplished my mission,” Potts said.

Potts grew up in Iowa but moved to Arizona. Coming back, she felt a large disparity between her two communities.

“Growing up in my younger adult life in Arizona, we really didn’t talk that much about culture because everybody is who they are. A person is person. So then coming back to Iowa, I would have thought things would have been more diverse and inclusive, but it’s starting. It’s really starting here, you know?” Potts said.

Of course, no growth can happen without conversation.

“I definitely feel like Ankeny has a lot of growing it can do, but I really feel like it’s hard to grow if you never talk about it. You can’t change things that you don’t discuss. Everybody just stays the same. There’s no conversations being had, so it won’t change,” Johnson said.

With the recent election of new leaders in the district, Potts is optimistic about the future.

“With the support of Dr. Pruitt and moving things forward, I think the district’s going to be in good hands for the next several years,” Potts said.

Future Goals

Currently, the district is working towards the equity goals they have created.

“We have developed some key indicators that will help educators and departments be more strategic and specific addressing academic and opportunity gaps,” Morris Jr. said.

Multiple schools in the district are making individual efforts to improve DEI for their students.

“I’ve set up some networks with different organizations, like the Ankeny Community Network, which does Juneteenth, and things like that, and Grandview, and DMACC, where some kids who wouldn’t get to see the college will see the college,” Johnson said.

Next year, she plans on expanding her equity group.

“The kids coming from Southview [next year] will have had me and been involved with the equity group. It will change the culture of the building,” Johnson said.

Over at Northview, Potts hopes to continue working with her student union. They meet every Wednesday.

Parkview and AHS have been gaining student feedback to create systems that will combat bullying and discrimination.

The hope is that within the next few years, the culture will continue to grow and change.

“I just hope the growth continues for supporting a diverse, inclusive community because the world is changing. People having an open mind and wanting to learn about various cultures is important,” Potts said.

The district believes that DEI is an integral part of their responsibility to improve student education.

“We’re living in a time where diversity, equity, inclusion is being co-opted into something that it’s not,” Morris Jr. said. “Diversity is just simply the differences that may make a difference. In the end, diversity, equity and inclusion is humanity work, and it is within our differences that lies our humanity.”